By JAN HANSPACH

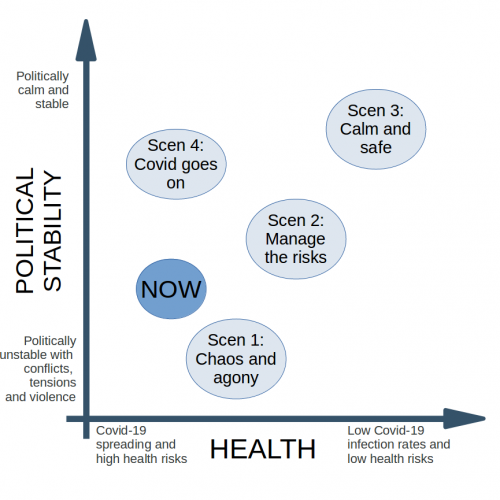

The global pandemic is influencing research in many different ways. Especially, projects that entail empirical field work suffer from a range of constraints and uncertainties. This is not different for our project – we had been looking forward to our first field season this year and couldn’t realize any of our well developed plans. Moreover, it is pretty unclear how the situation will develop and when and under which circumstances empirical and field based research can commence. So, what can we do about it? Wait and hope for the best? Well, we decided to run a small scenario planning exercise in order to have a structured conversation about the different options and strategies. Scenario planning is a method that has been designed to facilitate planning for complex systems in uncertain situations. For this, we roughly followed the method of exploratory scenario planning as described by Henrichs et al. (2010). And here is what we came up with for how our research in our case study area in Bolivia might develop.

1. Identify the main issues and identify driving forces and their impact

Obviously, the direct health risk from the global spread of Covid-19 is one of the key issues that has, together with regulations such as travel restrictions, fundamentally reduced our abilities to do field work and collect empirical data in 2020. It’s largely uncertain when and how it will be possible to resume field work and data collection. The currently unstable political situation in Bolivia is reinforcing the poor health situation and both together reduce the capacities (and possibly also the interests) of local actors and partners to participate in research. The delays and limited project time add additional pressure.

2. Identify critical uncertainties

We identified the political crisis in Bolivia, the spread of Covid-19 and the availability and impact of a vaccine as the critical uncertainties. These fundamentally influence our system and are, at the same time, highly uncertain.

3. Describe plausible scenario logics and the implications of the different scenarios

Based on these critical variables, we brainstormed different development pathways and finally condensed them to four different scenarios:

Important note: These scenarios are the result of an internal discussion process as a first step to cope with the situation. They do not necessarily contain the actual actions that will be taken. The next and more important steps are to discuss these issues with our research partners and, if possible, communities and carefully assess the risks and opportunities of future research.

Scenario 1: Chaos and agony

Main changes: The political situation in Bolivia remains chaotic and unstable, either because elections are further postponed or because election results are not widely accepted. Conflicts and violence paralyse the country. This reinforces the poor Covid-19 and health situation and poses serious health and security risks for both researchers and local communities. This situation also diminishes the capacity of local actors in Bolivia to collaborate or participate in research.

Implications for research: Even with an improvement of the Covid spread in Europe (vaccine and other health measures) and a lifting of international travel restrictions it will be difficult and risky to conduct field work in Bolivia. Little to no own data collection in Bolivia.

Strategies to adapt: Wait until the end of the year to see if elections happen and how the political situation in Bolivia develops. If no improvement takes place, evaluate alternative options for empirical data collection (e.g. via telephone, internet).

Scenario 2: Manage the risks

Main changes: Despite the fact that the elections take place and a new government is set up, strong political tensions and conflicts remain, because the election results are not accepted by parts of society. At the same time, the health situation somewhat stabilizes, e.g. because the infection rates drop due to beginning vaccinations (particularly in the global north) and effective protection measures.

Implications for research: Since international travel restrictions are lifted we can travel to Bolivia, but risks around logistics, health and capacities of communities to participate remain important issues.

Strategies to adapt: Continuous assessment and management of risks is required and field work needs to be thoroughly discussed and planned with partners. Risk management could include adapting research questions for relevance and feasibility, research methods and schedule. Most importantly, flexibility and resilience towards unexpected shocks must be key.

Scenario 3: Calm and safe

Main changes: The political situation in Bolivia calms down after the results of the October elections are widely accepted. This improves the implementation of hygiene and health measures and the supply with goods and other services. The fast availability of an effective vaccination, benefical mutations of dominant virus strains, and a better social-political adaptation improves the health situation on the global scale even if the vaccine is not broadly accessible in Bolivia. Therefore, international travel restrictions are soon lifted and the risks of fieldwork reduce significantly.

Implications for research: Travel and research in Bolivia is possible again in 2021, but requires some management and adaptations to the remaining health risks.

Strategies to adapt:

Management plan for health risks, some adaptation of methodology and schedule.

Scenario 4: Covid goes on

Main changes: The political situation in Bolivia calms down after the results of the October elections were widely accepted, but the Covid-19 situation does not improve. Case numbers continue to be high both within Bolivia and on the global scale and the virus doesn‘t mutate to less aggressive effects. The development of an efficient vaccine is delayed. Therefore travel restrictions persist.

Implications for research: Travel to Bolivia is not possible for us in the next three years.

Strategies to adapt: Evaluate alternative options for empirical data collection. Set deadlines for when decisions for alternative data collection will be taken.

4. Which general conclusions can we draw across all scenarios?

After looking at the implications of the individual scenarios, we had the feeling that many of the strategies are cross cutting and thus relevant for our overall strategy. Summarizing these we ended up with the following:

- Be adaptive and flexible – adapt research questions, design and methods according to the situation and be flexible with timing.

- Manage the risks – especially health risks need thorough management, but also the political situation can cause risks.

- Monitor and communicate – the situation needs to be regularly reassessed and adaptations and risk management require increased communication efforts with partners and within the team.

While these might have been obvious from the beginning, the planning process nevertheless helped us to think through different development pathways, to express our concerns and collect ideas for possible solutions (not all of our results are summarized here). In the end, it left us with the feeling that, despite all the uncertainty, we are not without agency. In fact, there are many different ways how we still can influence the outcomes of the research process. Also, we put a rough time line together for when we will have the next planning meetings in which we would re-assess the situation and take decisions for how to proceed. Until then we keep ourselves busy with literature reviews (like many others probably), we wait and, yes, we hope for the best. And if our hopes do not come true, we still have a plan for what to do next.

References:

Henrichs, T., M. Zurek, B. Eickhout, K. Kok, C. Raudsepp-Hearne, T. Ribeiro, D. van Vuuren, and A. Volkery. 2010. Scenario develoment and analysis for forward-looking ecosystem assessments. Pages 151-220 in N. Ash, H. Blanco, C. Brown, K. Garcia, T. Henrichs, N. Lucas, C. Raudsepp-Hearne, R. D. Simpson, R. Scholes, T. P. Tomich, B. Vira, and M. Zurek, editors. Ecosystems and human well-being: a manual for assessment practitioners. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.