Exploring the future of farming and biodiversity in agricultural landscapes in Australia. Part 2

About The project ‘The future of farming and biodiversity in agricultural landscapes’:

The Muttama Creek Catchment area’ seeks to explore options to integrate profitable farming and successful biodiversity conservation in the future (see link). The study area is a mixed farming landscape in south-eastern Australia. The project team consists of project leader Jan Hanspach, PhD student Tamara Schaal and partners at the Australian National University in Canberra (Australia).

This year the research team ran two workshops to bring together local communities and to explore the future for farming and biodiversity in the study area. The workshops served to discuss preferred futures and which actions can be taken individually and collaboratively to move towards the desired futures.

This blogpost focuses on the first workshop which took place on 29 April 2021.

If you want to find out more about the project, visit the project website or facebook page.

Our workshop facilitator Paul Ryan from the Australian Resilience Centre created a video of this workshop which you can find at the end of the blogpost.

In this project, we focused on the Muttama Creek Catchment area, a farming landscape in south-eastern Australia approximately 160 north west of the capital city of Canberra. Our research area is part of the so-called sheep-wheat belt which means that there is a mix of livestock grazing (mostly sheep and cattle) and commercial crop production (e.g. wheat and canola). The area is for the most part slightly hilly and rocky areas can be found for example on the hills. As agricultural land use dominates in the area, only remnant native vegetation, e.g. old eucalyptus trees, can be found. The photo below gives you an idea of what it looks like there.

Our decision to focus on this particular area was due to our collaboration with the Muttama Creek Landcare Group. It was formed in late 2018 by a group of local land managers and holders to protect biodiversity and deal with climate volatility in the area. We partnered with the Landcare Group in the organization of the two workshops.

The focus of the first workshop was to create a joint understanding of what the local community perceives to be the current key issues and what makes up a positive future for them.

Horizon 1 – The prominent system

In the first workshop, participants identified signs that the current system is unsustainable in the long run. From that, the following main issues emerged:

- External drivers of change pose threats to farming and biodiversity (e.g. climate change)

- “Traditional” farming approaches are not fit for future (e.g. resistant weeds, parasites)

- Community health and capacity are declining (e.g. ageing population)

- Water cycle is broken (e.g. poor water quality)

- Health of the farming system is at risk (e.g. soil health decline)

- Biodiversity loss is ongoing (e.g. old trees disappear from the landscape)

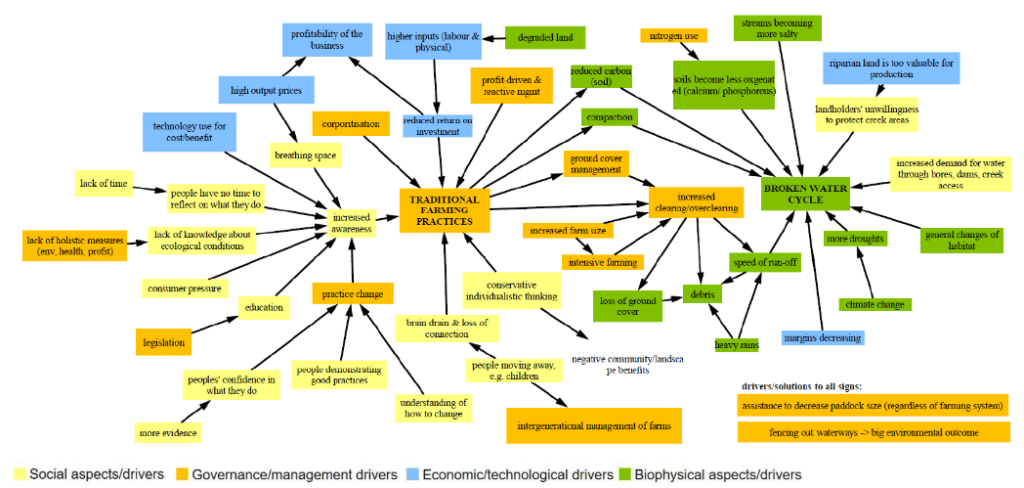

In the second step, participants discussed the underlying drivers causing these challenges. Many of these drivers are interconnected and we tried to capture these links through a mindmap that we, the researchers, created after the workshop (see Fig. 1)

The drivers are interconnected and we grouped them into four different categories. Social aspects are often linked to governance and management aspects. For example, people are leaving rural communities, which leads to challenges regarding the intergenerational management of the farms. Economic aspects, such as business profitability as well as input and output prices quite strongly shape to which degree land managers stick to traditional farming practices. The broken water cycle, which is caused among other things by over-clearing, was a biophysical aspect that played a prominent role in the group discussions.

Of course, there are also many things that the participants want to retain from the current systems. This included:

- Different skills & technologies (e.g. adoption of new technology)

- Environmental stewardship & cultural heritage (e.g. reward for good practice)

- Food production (e.g. locally produced food)

- Family farming (e.g. family creates farms and farms create family)

- Vibrant communities (e.g. connection to land, people, animals)

- Governance support (e.g. good biosecurity legislation in place)

- Independence & Freedom (e.g. democracy)

Horizon 3 – The desirable futures

“I guess to me it’s that idea that when we’re in the future we won’t know when we’ve arrived, it’ll be a continuous thing of we are looking at the new way and a better way.”

(participant during first workshop)

This quote highlights how Three Horizons doesn’t focus on one definite endpoint in the future but supports a consciousness of the future in the present. The future is uncertain and one cannot know what it will look like. One of the key advantages of Three Horizons is to support communities to consider how they can bring about change. Therefore, participants discussed where they would like to move towards in the future and which elements of such positive futures (seeds) exist today:

- Science and Technology (e.g. drones in agriculture)

- Increase in capacities and knowledge (e.g. education about regenerative farming practices)

- Ethical and responsible farming (e.g. food labelling)

- Economic opportunities and viability / Community Wellbeing (e.g. eco-and agritourism in rural areas)

- Balanced, resilient, healthy and (bio)diverse farm-, ecosystem (e.g. cover crops or rewards for good environmental stewardship)

The feedback that we received from participants (see below) after the workshop showed that most people felt enthusiastic after the workshop. However, some people raised concerns about how people beyond the group of participants could be engaged and what is next.

“Interesting day – there is hope for the future!”

“Get rid of my friends they hold me back.”

The next blogpost will explain how, based on these discussions, participants developed pathways into the future through storytelling.

[1] Seed is an umbrella term which refers to “initiatives (social, technological, economic, or social–ecological ways of thinking or doing) that exist […] but are not currently dominant or prominent in the world.” (Bennett et al. 2016, p. 442).

References

Bennett, E. M., M. Solan, R. Biggs, T. McPhearson, A. V. Norström, P. Olsson, L. Pereira, G. D. Peterson, C. Raudsepp‐Hearne, F. Biermann, S. R. Carpenter, E. C. Ellis, T. Hichert, V. Galaz, M. Lahsen, M. Milkoreit, B. Martin López, K. A. Nicholas, R. Preiser, G. Vince, J. M. Vervoort, and J. Xu. 2016. Bright spots: seeds of a good Anthropocene. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14(8):441–448.

Mitchell M.; Lockwood M.; Moore S.A.; Clement S. (2015): Incorporating governance influences into social-ecological system models: a case study involving biodiversity conservation. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 58 (11): 1903–1922.

Pingback: NEWSLETTER - PECS