Consensus decision making enables all members of a group to reach an agreement. Instead of having an authority rule or a majority vote, which often neglects individuals or minorities, a consensus decision ensures that everyone can actively support it, or at least live with it. If everyone agrees to a decision there will be much more commitment to its implementation. Most importantly, group members have the option to block proposals in a consensus decision making process, meaning the proposal has to be amended or a whole new proposal needs to be worked out before a decision can be made. Consensus decision making can be applied in many fields. It can be especially useful in transdisciplinary research, since it requires decision-making processes in the design and implementation of the research objectives and methods.

It sounds like an ideal democratic procedure, but how does it work? When hearing about consensus decision making for the first time people often think it just takes forever and isn’t effective. It is true that the process can sometimes take longer than, for example, a majority vote, but it makes it much more likely that really good decisionsare made and no time is wasted on later fixing the results of poor decisions. Also, experienced groups are usually very fast and there are lots of ways to facilitate an effective and efficient decision making process.

There are some requirements for the group and the individuals in order for a consensus process to work. First, the group needs to have a common goal, such as a shared vision or an action to be taken, and everyone needs to be committed to reaching consensus. This last may sound obvious, but it means everyone really has to have patience, invest time and energy into among the group, and therefore be willing to let go of some personal wishes in favor of what’s best for the group as a whole. For this to work, mutual trust is necessary so that everyone can openly express their thoughts and needs. And yes, reaching consensus can sometimes take a while and sufficient time should be planned in. Because there are some variations to implementing a consensus process, it is also very important that the steps and special features are clear to everyone or that they are clearly explained in advance. And last but not least, active participation of all group members is key. So the consensus principle is not just a decision-making framework, it requires a general attitude and willingness to be an equal part of a group and to put aside hierarchies and prejudices.

Having lived in community projects based on the consensus principle for many years, I have gained some experience in applying and facilitating consensus processes. I can say that an experienced group definitely becomes more efficient over time, but it is still a lot of work. The process even rarely comes up against insurmountable limits, which can, for example, lead to a person leaving the group, a painful, yet sometimes necessary step. For important decisions I would nevertheless always prefer it to other supposedly democratic processes, for the above reasons.

The basic steps of the consensus process

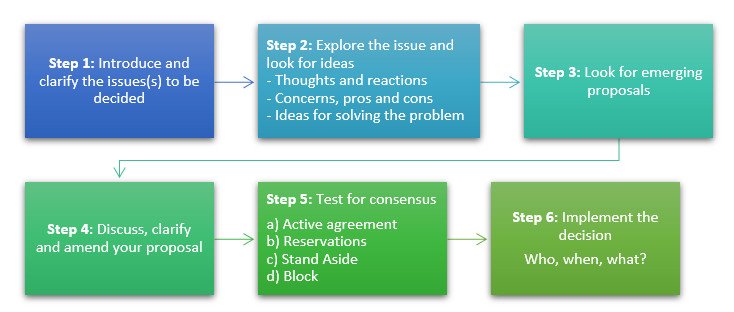

The process of decision making itself usually follows six steps (see figure), which can be somewhat interchanged, depending on the decision at hand, the preferences of the group, or whether a proposal was already framed beforehand. Usually, the issue is first introduced and there is the opportunity to ask questions in terms of content, without already expressing opinions. In the second step the issue is further explored and discussed and all opinions can be expressed. In the third step proposals are developed on the basis of the discussion and then narrowed down to one proposal, which is then, in step 4, discussed, clarified, and amended if need be.

To find out more about the details of the steps, have a look here.

Step 5, testing for consensus is where the actual decision making takes place. Everyone should state one of the four options. Blocks stop a proposal from happening, which means a whole new proposal needs to be made. This is obviously the toughest option and comes with a lot of responsibility. Ideally, a block is unnecessary, if there was a good discussion in the beginning. Standing aside means you cannot support the proposal, but you won’t stand in the way of the group to implement it without you. Reservations also are a way of expressing concerns, but you will still go along with the group’s decision.

Usually, if there are no blocks, not too many stand asides or reservations, and lots of active agreement you have reached consensus!

Consensus making and transdisciplinarity

What does consensus making have to do with transdisciplinary research? Transdisciplinarity is a way of doing science which is becoming more and more popular. It embraces the integration of scientists from all different disciplines and backgrounds and non-academic stakeholders from businesses, government and the civil society within the research process (Lang et al. 2012). Right from the beginning of a transdisciplinary project all actors are supposed to work together at eye level and jointly make important decisions, e.g. on the goals of a project or the specific methods.

So, transdisciplinary research projects by definition are based on similar principals as consensus decision making. Unfortunately, this ideal is rarely achieved. Because of organizational or administrative processes of the participating research partners there are often limited possibilities for joint design, action and decision-making, thus the consensus principle is often not or only halfheartedly applied (Hanschitz et al. 2009).

Furthermore, academic actors often have a limited flexibility, because they have to follow the guidelines of the funding agency, who has agreed to a specific research plan with a fixed timetable and methods.

Also, academic actors often are used to being in control of the research process, write the meeting minutes, facilitate the discussions, publish the results. Close attention should be paid to equally distributing these tasks, for what is communicated and in what form is to some extent in the hands of the person carrying out these tasks (Hanschitz et al. 2009). Consequently, consensus also means being able to let go of one’s own ideas, academic backgrounds, visions and wishes to a certain degree, because radical opponents have no place and no time in participation processes, their premises are not contained in the logic of the system (Seeds for change 2013, Hanschitz 2009).

I think that more transdisciplinary AND consensus based research should be carried out and more efforts should be put into overcoming barriers for consensus in research collaborations, so that these can become truly collaborative. I think consensus decision making as described here can be a useful practical tool for making a more real transdisciplinary approach possible, especially in constrained contexts, which are limited for example by institutional structures and funding agencies.

Such genuine consensus projects can be very empowering for all participants, so that not only decisions are jointly made, but also that research outcomes and successes are equally shared.

Contact: drewssha@leuphana.de

Resources:

Hanschitz, R.-C., Schmidt, E., Schwarz, G. (2009). Transdisziplinarität in Forschung und Praxis: Chancen und Risiken partizipativer Prozesse. Wiesbaden.

LANG, D. J., WIEK, A. & BERGMANN, M. et al. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science 7, 25–43.

Seeds for change (2013): A Consensus Handbook: Co-operative Decision-Making for Activists, Co-ops and Communities